0.0.1 ↑ Alkohole

Alkohole enthalten neben den Elementen C und H auch O. Sie "leiten" sich aber dennoch von den Kohlenwasserstoffen "ab".

Beispiel: \text{C}_2\text{H}_6\text{O} als Summenformel

Strukturformel:

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & | & & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & - \\ {} & | & & | & & & \end{array} oder \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & & & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & & & | & \end{array}?

- Versuch

[Zugabe von Natrium zu Wasser und \text{C}_2\text{H}_6\text{O}]

- Beobachtung

[Jeweils] exotherme Reaktion unter Gasentwicklung (\text{H}_2)

- Folgerung

\text{Na} + \text{H}_2\text{O} \longrightarrow \text{H}_2\uparrow + \,\text{Na}^+\text{OH}^-

\text{Na} + \text{C}_2\text{H}_6\text{O} \longrightarrow \text{C}_2\text{H}_5\text{O}^-\text{Na}^+ + \text{H}_2\uparrow

Da vergleichbares Reaktionsprinzip, muss auch die Verbindung vergleichbar zu Wasser sein.

2 \,{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccc} {} \text{H} & \rightarrow & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} \\ {} & & \uparrow \\ {} & & \text{H} \end{array} } \stackrel{\text{Abspaltung von H als H}^+}{\longrightarrow} \text{H}_2 + 2 \,\text{OH}^-

(leichte Abspaltung, da Bindung bereits polar!)

2 \,{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & | & & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\text{O}} & | \\ {} & | & & | & & \uparrow & \\ {} & & & & & \text{H} & \end{array} } \stackrel{\text{Abspaltung von H als H}^+}{\longrightarrow} \text{H}_2 + 2 \,\text{C}_2\text{H}_5\text{O}^-

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & & & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & & & | & \end{array}

Keine polare [H-]Bindung; unwahrscheinlich als Struktur

0.0.1.1 ↑ Alkohole im Überblick

Alkohole leiten sich formal von den einfachen Kohlenwasserstoffen ab. Es existiert ebenfalls eine homologe Reihe.

| Formel | Bezeichnung |

|---|---|

| \text{CH}_4\text{O} | Methanol |

| \text{C}_2\text{H}_6\text{O} | Ethanol |

| \text{C}_3\text{H}_8\text{O} | Propanol |

| \text{C}_4\text{H}_{10}\text{O} | Butanol |

Formel:

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{cccccc} {} & & | & & & \\ {} \text{R} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{O} & \text{H} \\ {} & & | & & & \end{array}

\text{OH}: Hydroxiegruppe [ist eine] funktionelle Gruppe, ändert die Eigenschaften

Mehrwertige Alkohole [besitzen] mehr als eine OH-Funktion im Molekül. Beispiele:

- Ethandiol

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccc} {} & | & & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & \\ {} \text{H} & \text{O} & & \text{O} & \text{H} \end{array}

- (1,2,3-)Propantriol

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & | & & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & & | & \\ {} \text{H} & \text{O} & & \text{O} & \text{H} & \text{O} & \text{H} \end{array}

- Primäre Alkohole

[C-Atom mit OH-Gruppe bindet genau ein C-Atom]

- [prim-Ethanol]

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccc} {} & | & & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & \text{\textbf{--}} & \text{\textbf{C}} & - \\ {} & | & & | & \\ {} & & & \text{O} & \text{H} \end{array}

- prim-Propanol

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccccc} {} & | & & | & & | & & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & \text{\textbf{--}} & \text{\textbf{C}} & - & \text{O} & \text{H} \\ {} & | & & | & & | & & & \end{array}

- Sekundäre Alkohole

[C-Atom mit OH-Gruppe bindet genau zwei C-Atome]

- [sek-Propanol]

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & | & & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & \text{\textbf{--}} & \text{\textbf{C}} & \text{\textbf{--}} & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & & | & \\ {} & & & \text{O} & \text{H} & & \end{array}

- sek-Butanol, 2-Butanol, Butan-2-ol

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccccc} {} & | & & | & & | & & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & \text{\textbf{--}} & \text{\textbf{C}} & \text{\textbf{--}} & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & & | & & | & \\ {} & & & & & \text{O} & \text{H} & & \end{array}

- Tertiäre Alkohole

[C-Atom mit OH-Gruppe bindet genau drei C-Atome]

- tet-Butanol, 2-Methylpropan-2-ol

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & & | & & & \\ {} & & - & \text{C} & - & & \\ {} & | & & \text{\textbf{\texttt{|}}} & & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & \text{\textbf{--}} & \text{\textbf{C}} & \text{\textbf{--}} & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & & | & \\ {} & & & \text{O} & \text{H} & & \end{array}

Die OH-Funktion ändert (je nach Lage im Molekül) die Eigenschaften eines Moleküls.

[Zwei OH-Gruppen an einem C-Atom sind normalerweise nicht stabil, weil wegen der Elektronegativität des Sauerstoffs "zu wenig" Elektronen verfügbar wären (es findet eine "zu starke" Polarisierung statt)]

0.0.1.2 ↑ Eigenschaften der Alkohole

Die Eigenschaften der Alkohole sind durch das Vorhandensein "einer" OH-Funktion bestimmt.

- Löslichkeit

Ethanol ist im Vergleich zu Ethan in Wasser löslich (hydrophil).

Erklärung: Ethanol ist ein polares Molekül:

- Ethan

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccc} {} & | & & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & \end{array}

Keine e^--Verschiebung; keine Polarität

- Ethanol

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & | & & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & \rightarrow & \text{O} & \text{H} \\ {} & | & & | & & & \end{array}

e^--Verschiebung; Polarität → Lösbarkeit im polaren Lösungsmittel \text{H}_2\text{O} (Umhüllung des [gesamten] Moleküls mit Wasserteilchen möglich)

Achtung: Je länger die C-Kette, desto mehr dominiert der unpolare Teil → Löslichkeit sinkt [ab \text{C}_{10} überhaupt keine Löslichkeit mehr]

- Siedepunkt/Schmelzpunkt

Im Vergleich zu Alkanen sind Siedepunkt/Schmelzpunkt deutlich erhöht.

Es wird folglich mehr Energie benötigt, um Moleküle voneinander zu trennen.

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccccccccccc} {} & | & & | & & {\scriptsize\delta^{-}} & & & & {\scriptsize\delta^{+}} & & & & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\text{O}} & | & \cdots\cdots & & \text{H} & & & & & \\ {} & | & & | & & | & & & & | & & | & & | & \\ {} & & & & & \text{H} & & \cdots\cdots & | & \underline{\text{O}} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & & & & & {\scriptsize\delta^{+}} & & & & {\scriptsize\delta^{-}} & & | & & | & \end{array}

[Voraussetzung für Wasserstoffbrückenbindung: stark negativ polarisiertes Atom mit freien Elektronenpaaren und H-Atom]

Wasserstoffbrücken als sehr starke Wechselwirkung zwischen Molekülen sorgen für hohe Siedepunkte/Schmelzpunkte.

[Die Wasserstoffbrückenbindung ist deshalb so stark, weil sie a) deutlich lokalisiert und b) permanent ist.]

- Viskosität

Durch Wasserstoffbrücken werden Alkohole viskoser als vergleichbare Alkane.

- Brennbarkeit

Ethanol brennt mit nicht rußender blauer Flamme.

→ \text{C}:\text{O}-Anteil; C schon teilweise oxidiert!

0.0.1.3 ↑ Oxidierbarkeit von Alkoholen

Grundlage: Oxidationszahl (gedachte Ladungszahl → e^- an Atom)

Beispiel: \text{H}_2\text{S}

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} \text{H} & ( & - & \overline{\underline{\text{S}}} & - & ) & \text{H} \end{array}

Vorstellung als "Ionen":

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccc} {} \text{H}^{+} & \text{S}^{2-} & \text{H}^{+} \end{array}

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccc} {} _{+1} & & _{-2} & & _{+1} \\ {} \text{H} & - & \text{S} & - & \text{H} \end{array}

Für Kohlenstoffverbindungen gilt:

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccccccccccc} {} & & & _{+1} & & & & _{+1} & & & & _{+1} & & & \\ {} & & & \text{H} & & & & \text{H} & & & & \text{H} & & & \\ {} & & & \frown & & & & \frown & & & & \frown & & & \\ {} _{+1} & & & | & _{-3} & & & | & & & _{-3} & | & & & _{+1} \\ {} \text{H} & ( & - & \text{C} & - & | & - & \text{C} & - & | & - & \text{C} & - & ) & \text{H} \\ {} & & & | & & & & | & _{-2} & & & | & & & \\ {} & & & \smile & & & & \smile & & & & \smile & & & \\ {} & & & \text{H} & & & & \text{H} & & & & \text{H} & & & \\ {} & & & _{+1} & & & & _{+1} & & & & _{+1} & & & \end{array}

- Primärer Alkohol

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccccccc} {} & & & \text{H} & & & _{+1} & \text{H} & & & \\ {} & & & \frown & & & & \frown & & & \\ {} & & & | & & & & | & & & \\ {} \text{H} & ( & - & \text{C} & - & | & - & \text{C} & ( & - & \stackrel{-2}{\overline{\underline{\text{O}}}}\stackrel{+1}{\text{H}}\}_{{-}{1}} \\ {} & & & | & & & _{-1} & | & & & \\ {} & & & \smile & & & & \smile & & & \\ {} & & & \text{H} & & & _{+1} & \text{H} & & & \end{array}

[In der XHTML-Version fehlt hier eine Formel. In der PDF-Version ist sie vorhanden.] - Sekundärer Alkohol

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & & _{+1} & & & \\ {} & | & & | & _{\pm 0} & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & & | & \\ {} & & _{-1}\{ & \text{O} & \text{H} & & \end{array}

[In der XHTML-Version fehlt hier eine Formel. In der PDF-Version ist sie vorhanden.] - Tertiärer Alkohol

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & & | & & & \\ {} & & - & \text{C} & - & & \\ {} & | & & | & _{+1} & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & & | & \\ {} & & _{-1}\{ & \text{O} & \text{H} & & \end{array}

[In der XHTML-Version fehlt hier eine Formel. In der PDF-Version ist sie vorhanden.]

- Versuch

\text{Primärer Alkohol} + \text{CuO} \longrightarrow \text{Cu} + \text{?}

Primrer Alkohol + CuO → Cu + ? \text{Sekundärer Alkohol} + \text{CuO} \longrightarrow \text{Cu} + \text{?}

Sekundrer Alkohol + CuO → Cu + ? \text{Tertiärer Alkohol} + \text{CuO} \not\longrightarrow

Tertirer Alkohol + CuO ̸x→

{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & | & _{-1} & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & \text{H} \\ {} & | & & | & & & \end{array} } \,+ {\stackrel{+2}{\text{Cu}}}\text{O} \longrightarrow\ \stackrel{0}{\text{Cu}} + { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{cccccc} {} & & & & & \stackrel{-2}{\overline{\text{O}}|} \\ {} _{-3} & | & & & /\!/ & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & _{+1} & \\ {} & | & & & \backslash{} & \\ {} & & & & _{+1} & \text{H} \end{array} }

∣ ∣ − 1 − C − C − O ¯ ¯ H ∣ ∣ + Cu + 2 O → Cu 0 + O ¯ ∣ − 2 − 3 ∣ ∕ ∕ − C − C + 1 ∣ ∖ + 1 H -1 \longrightarrow +1

− 1 → + 1 Primäre Alkohole sind bereit, e^-

e − Exkurs: Aufstellen von Redoxgleichungen

Teilgleichungen mit Oxidationszahlen

e^-

e − Ladungsausgleich

Stoffausgleich

e^-

e −

- Reduktion

{\stackrel{+2}{\text{Cu}}}\text{O} + 2\,e^- + 2\,\text{H}_3\text{O}^+ \longrightarrow\ \stackrel{\pm 0}{\text{Cu}} +\ 3\,\text{H}_2\text{O}

Cu + 2 O + 2 e − + 2 H 3 O + → Cu ± 0 + 3 H 2 O - Oxidation

{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & | & _{-1} & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & \text{H} \\ {} & | & & | & & & \end{array} } \,+ 2\,\text{H}_2\text{O} \longrightarrow { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{cccccc} {} & & & & & \stackrel{-2}{\overline{\text{O}}|} \\ {} _{-3} & | & & & /\!/ & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & _{+1} & \\ {} & | & & & \backslash{} & \\ {} & & & & _{+1} & \text{H} \end{array} } + 2\,e^- + 2\,\text{H}_3\text{O}^+

∣ ∣ − 1 − C − C − O ¯ ¯ H ∣ ∣ + 2 H 2 O → O ¯ ∣ − 2 − 3 ∣ ∕ ∕ − C − C + 1 ∣ ∖ + 1 H + 2 e − + 2 H 3 O + - Gesamtgleichung

{\stackrel{+2}{\text{Cu}}}\text{O} + { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & | & _{-1} & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & \text{H} \\ {} & | & & | & & & \end{array} } \longrightarrow \text{Cu} + { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{cccccc} {} & & & & & \stackrel{-2}{\overline{\text{O}}|} \\ {} _{-3} & | & & & /\!/ & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & _{+1} & \\ {} & | & & & \backslash{} & \\ {} & & & & _{+1} & \text{H} \end{array} } + \text{H}_2\text{O}

Cu + 2 O + ∣ ∣ − 1 − C − C − O ¯ ¯ H ∣ ∣ → Cu + O ¯ ∣ − 2 − 3 ∣ ∕ ∕ − C − C + 1 ∣ ∖ + 1 H + H 2 O

- Reduktion

{\stackrel{+7}{\text{Mn}}}\text{O}_4^- + 5\,e^- + 8\,\text{H}_3\text{O}^+ \longrightarrow\ \stackrel{+2}{\text{Mn}}^{2+} +\ 12\,\text{H}_2\text{O}

Mn + 7 O 4 − + 5 e − + 8 H 3 O + → Mn + 2 2 + + 1 2 H 2 O - Oxidation

{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & | & _{-1} & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & \text{H} \\ {} & | & & | & & & \end{array} } \,+ 2\,\text{H}_2\text{O} \longrightarrow { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{cccccc} {} & & & & & \stackrel{-2}{\overline{\text{O}}|} \\ {} _{-3} & | & & & /\!/ & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & _{+1} & \\ {} & | & & & \backslash{} & \\ {} & & & & _{+1} & \text{H} \end{array} } + 2\,e^- + 2\,\text{H}_3\text{O}^+

∣ ∣ − 1 − C − C − O ¯ ¯ H ∣ ∣ + 2 H 2 O → O ¯ ∣ − 2 − 3 ∣ ∕ ∕ − C − C + 1 ∣ ∖ + 1 H + 2 e − + 2 H 3 O + - Gesamtgleichung

5\,{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & | & & | & _{-1} & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & \text{H} \\ {} & | & & | & & & \end{array} } + 10\,\text{H}_2\text{O} + 16\,\text{H}_3\text{O}^+ + 2\,\text{MnO}_4^- + 10\,e^- \longrightarrow 2\,\text{Mn}^{2+} + 24\,\text{H}_2\text{O} + 5\,{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{cccccc} {} & & & & & \stackrel{-2}{\overline{\text{O}}|} \\ {} _{-3} & | & & & /\!/ & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & _{+1} & \\ {} & | & & & \backslash{} & \\ {} & & & & _{+1} & \text{H} \end{array} } + 10\,e^- + 10\,\text{H}_3\text{O}^+

5 ∣ ∣ − 1 − C − C − O ¯ ¯ H ∣ ∣ + 1 0 H 2 O + 1 6 H 3 O + + 2 MnO 4 − + 1 0 e − → 2 Mn 2 + + 2 4 H 2 O + 5 O ¯ ∣ − 2 − 3 ∣ ∕ ∕ − C − C + 1 ∣ ∖ + 1 H + 1 0 e − + 1 0 H 3 O +

- Reduktion

{\stackrel{+6}{\text{Cr}}}_2\text{O}_7^{2-} + 6\,e^- + 14\,\text{H}_3\text{O}^+ \longrightarrow\ 2\,\stackrel{+3}{\text{Cr}}^{3+} +\ 21\,\text{H}_2\text{O}

Cr + 6 2 O 7 2 − + 6 e − + 1 4 H 3 O + → 2 Cr + 3 3 + + 2 1 H 2 O - Oxidation

{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & & \text{O} & \text{H} & & \\ {} & | & & | & _{\pm 0} & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & & | & \end{array} } \,+ 2\,\text{H}_2\text{O} \longrightarrow { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & ^{/} & \text{O} & ^{\backslash} & & \\ {} & | & & \vert\vert{} & _{+2} & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & & & | & \end{array} } + 2\,e^- + 2\,\text{H}_3\text{O}^+

O H ∣ ∣ ± 0 ∣ − C − C − C − ∣ ∣ ∣ + 2 H 2 O → ∕ O ∖ ∣ ∣ ∣ + 2 ∣ − C − C − C − ∣ ∣ + 2 e − + 2 H 3 O + - Gesamtgleichung

3\,{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & & \text{O} & \text{H} & & \\ {} & | & & | & _{\pm 0} & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & & | & \end{array} } + 6\,\text{H}_2\text{O} + \text{Cr}_2\text{O}_7^{2-} + 8\,\text{H}_3\text{O}^+ \longrightarrow { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & ^{/} & \text{O} & ^{\backslash} & & \\ {} & | & & \vert\vert{} & _{+2} & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & & & | & \end{array} } + 17\,\text{H}_2\text{O} + 2\,\text{Cr}^{3+}

3 O H ∣ ∣ ± 0 ∣ − C − C − C − ∣ ∣ ∣ + 6 H 2 O + Cr 2 O 7 2 − + 8 H 3 O + → ∕ O ∖ ∣ ∣ ∣ + 2 ∣ − C − C − C − ∣ ∣ + 1 7 H 2 O + 2 Cr 3 +

{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & & \text{O} & \text{H} & & \\ {} & | & & | & _{\pm 0} & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & | & & | & \end{array} } \,+ {\stackrel{+2}{\text{Cu}}}\text{O} \longrightarrow\ \stackrel{0}{\text{Cu}} + { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & ^{/} & \text{O} & ^{\backslash} & & \\ {} & | & & \vert\vert{} & & | & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - \\ {} & | & & & & | & \end{array} }

O H ∣ ∣ ± 0 ∣ − C − C − C − ∣ ∣ ∣ + Cu + 2 O → Cu 0 + ∕ O ∖ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ − C − C − C − ∣ ∣ Sekundäre Alkohole sind bereit, e^-

e −

0.0.1.4 ↑ Oxidationsprodulte der Alkohole

\text{Primärer Alkohol} \stackrel{\text{Ox.}}{\longrightarrow} \text{Aldehyd}

Primrer Alkohol → Ox. Aldehyd Mit funktioneller Gruppe:

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccc} {} & & & \overline{\text{O}}| & {\scriptsize\delta^-} \\ {} & & /\!/ & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & & & \\ {} {\scriptsize\delta^+} & & \backslash{} & & \\ {} & & & \text{H} & \end{array}

O ¯ ∣ δ − ∕ ∕ − C δ + ∖ H Name: Stammname–al

\text{Sekundärer Alkohol} \stackrel{\text{Ox.}}{\longrightarrow} \text{Keton}

Sekundrer Alkohol → Ox. Keton Mit funktioneller Gruppe (Carbonylgruppe [auch Ketofunktion]):

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccc} {} ^{/} & \text{O} & ^{\backslash} \\ {} & \vert\vert{} & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - \end{array}

∕ O ∖ ∣ ∣ − C − Name: Stammname–on

0.0.1.5 ↑ [Physikalische] Eigenschaften der Oxidationsprodukte der Alkohole (im Vergleich)

- Siedepunkt/Schmelzpunkt

Siedepunkt/Schmelzpunkt bei Aldehyden und Ketonen vergleichbar (durch ähnliche Polarität der funktionellen Gruppe).

Im Vergleich zu Alkoholen niedrigerer Siedepunkt/Schmelzpunkt, da nur Polarität, aber keine Wasserstoffbrücken.

[Je länger die Kette, desto mehr V.d.W.-Kräfte, desto höhere Siedepunkte/Schmelzpunkte]

- Löslichkeit

Niedrigere Vertreter sind aufgrund der polaren Gruppen in Wasser löslich; durch längere Kohlenstoffketten sinkt die Löslichkeit in Wasser, während sie in Benzin zunimmt.

- Viskosität

Die Viskosität nimmt mit steigender Kettenlänge zu [V.d.W.-Kräfte!], ist aber nicht so stark wie bei den Alkoholen.

0.0.1.6 ↑ Chemische Eigenschaften der Oxidationsprodukte der Alkohole

- Aldehyde

- a)

mit ammoniakalischer Silbernitratlösung

- Reduktion

\text{Ag}^+ + e^- \longrightarrow \text{Ag}

Ag + + e − → Ag - Oxidation

{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccc} {} & & & & \overline{\text{O}}| \\ {} & & & /\!/ & \\ {} \text{R} & - & \text{C} & & \\ {} & & & \backslash{} & \\ {} & & & & \text{H} \end{array} } + 2\,\text{OH}^- \longrightarrow { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & & & \overline{\text{O}}| & & \\ {} & & & /\!/ & & & \\ {} \text{R} & - & \text{C} & & & & \\ {} & & & \backslash{} & & & \\ {} & & & & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & - & \text{H} \end{array} } + 2\,e^- + \text{H}_2\text{O}

O ¯ ∣ ∕ ∕ R − C ∖ H + 2 OH − → O ¯ ∣ ∕ ∕ R − C ∖ O ¯ ¯ − H + 2 e − + H 2 O

- b)

mit Fehling I- und II-Lösung

- Reduktion

2\,\text{Cu}^{2+} + 2\,e^- + 2\,\text{OH}^- \longrightarrow \text{Cu}_2\text{O} + \text{H}_2\text{O}

2 Cu 2 + + 2 e − + 2 OH − → Cu 2 O + H 2 O - Oxidation

{ \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccc} {} & & & & \overline{\text{O}}| \\ {} & & & /\!/ & \\ {} \text{R} & - & \text{C} & & \\ {} & & & \backslash{} & \\ {} & & & & \text{H} \end{array} } + 2\,\text{OH}^- \longrightarrow { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & & & \overline{\text{O}}| & & \\ {} & & & /\!/ & & & \\ {} \text{R} & - & \text{C} & & & & \\ {} & & & \backslash{} & & & \\ {} & & & & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & - & \text{H} \end{array} } + 2\,e^- + \text{H}_2\text{O}

O ¯ ∣ ∕ ∕ R − C ∖ H + 2 OH − → O ¯ ∣ ∕ ∕ R − C ∖ O ¯ ¯ − H + 2 e − + H 2 O

→ Aldehyde lassen sich oxidieren!

- Ketone

Ketone lassen sich weder durch die sog. Fehlingprobe noch durch eine Silberspiegelprobe weiter oxidieren.

Damit gilt: Die Fehlingprobe und die Silberspiegelprobe sind spezifische Nachweisreaktionen für Aldehydfunktionen.

[Die Fehlingprobe ist bei ziegelrotem Ausschlag (\text{Cu}_2\text{O}

Cu 2 O

0.0.1.7 ↑ [Übersicht]

\begin{array}{@{}lclcl} {} \text{Primäre Alkohole} &\stackrel{\text{Ox.}}{\longrightarrow}& {} \text{Aldehyde} &\stackrel{\text{Ox.}}{\longrightarrow}& {} \text{Carbonsäuren} \\ {} { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{cccccc} {} & & | & & & \\ {} \text{R} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{O} & \text{H} \\ {} & & | & & & \end{array} } &\stackrel{\text{Ox.}}{\longrightarrow}& {} { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccc} {} & & & & \overline{\text{O}}| \\ {} & & & /\!/ & \\ {} \text{R} & - & \text{C} & & \\ {} & & & \backslash{} & \\ {} & & & & \text{H} \end{array} } &\stackrel{\text{Ox.}}{\longrightarrow}& {} { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccccc} {} & & & & \overline{\text{O}}| & & \\ {} & & & /\!/ & & & \\ {} \text{R} & - & \text{C} & & & & \\ {} & & & \backslash{} & & & \\ {} & & & & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}} & - & \text{H} \end{array} } \text{(Carboxylgruppe)} \end{array}

Primre Alkohole → Ox. Aldehyde → Ox. Carbonsuren ∣ R − C − O H ∣ → Ox. O ¯ ∣ ∕ ∕ R − C ∖ H → Ox. O ¯ ∣ ∕ ∕ R − C ∖ O ¯ ¯ − H (Carboxylgruppe) [Wenn man Aldehyde haben will, darf man primäre Alkohole nur mäßig oxidieren – oxidiert man zu stark, erhält man Carbonsäuren.]

\begin{array}{@{}lclc} {} \text{Sekundäre Alkohole} &\stackrel{\text{Ox.}}{\longrightarrow}& {} \text{Ketone} &\not\longrightarrow \\ {} { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{cccccc} {} & & \text{R}' & & & \\ {} & & | & & & \\ {} \text{R} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{O} & \text{H} \\ {} & & | & & & \end{array} } &\stackrel{\text{Ox.}}{\longrightarrow}& {} { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{ccccc} {} & ^{/} & \text{O} & ^{\backslash} & \\ {} & & \vert\vert{} & & \\ {} \text{R}' & - & \text{C} & - & \text{R} \end{array} } &\not\longrightarrow \end{array}

Sekundre Alkohole → Ox. Ketone ̸x→ R ′ ∣ R − C − O H ∣ → Ox. ∕ O ∖ ∣ ∣ R ′ − C − R ̸x→ \begin{array}{@{}lc} {} \text{Tertiäre Alkohole} &\not\longrightarrow \\ {} { \setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{cccccc} {} & & \text{R}' & & & \\ {} & & | & & & \\ {} \text{R} & - & \text{C} & - & \text{O} & \text{H} \\ {} & & | & & & \\ {} & & \text{R}'' & & & \end{array} } &\not\longrightarrow \end{array}

Tertire Alkohole ̸x→ R ′ ∣ R − C − O H ∣ R ′ ′ ̸x→ [Oxidiert man teritäre Alkohole (mit einem sehr starken Oxidationsmittel), so zerfällt das Ding.]

→ Unterscheidungsmöglichkeit von Alkoholen und deren Oxidationsprodukten!

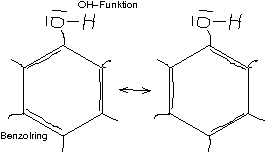

0.0.1.8 ↑ Phenol – ein besonderer Alkohol

Aromatisierter Alkohol → Mesomeriestabilisierung

Aromatischer Alkohol mit mesomeren Grenzformeln → nicht oxidierbar!

reagiert sauer → Protonendonator

Erklärung:

\text{CH}_3{-}\text{CH}_2{-}\text{OH} + \text{H}_2\text{O} \not\longrightarrow \text{H}_3\text{O}^+ + \text{CH}_3{-}\text{CH}_2{-}\overline{\underline{\text{O}}}|^\ominus

Warum gibt Phenol leichter ein Proton ab als andere Alkohole?

[Beim Ethanoation ist die] negative Ladung lokalisiert [ungut]:

\setlength{\arraycolsep}{0pt} \begin{array}{cccccc} {} & | & & | & & \\ {} - & \text{C} & - & \text{C} & - & \overline{\underline{\text{O}}}|^\ominus \\ {} & | & & | & & \end{array}

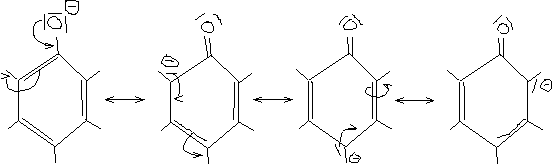

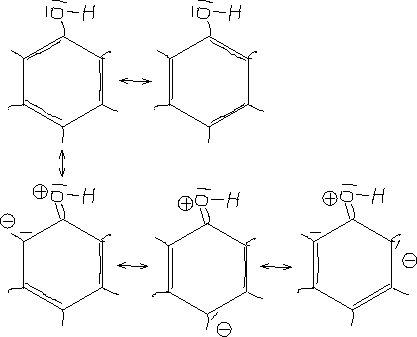

[Beim Phenolation dagegen ist die] negative Ladung über das gesamte Molekül delokalisiert [und] damit energetisch günstiger:

Es reagiert leicht sauer (gibt Proton nicht sehr leicht ab).

Mesomeriestabilisierung von Phenol

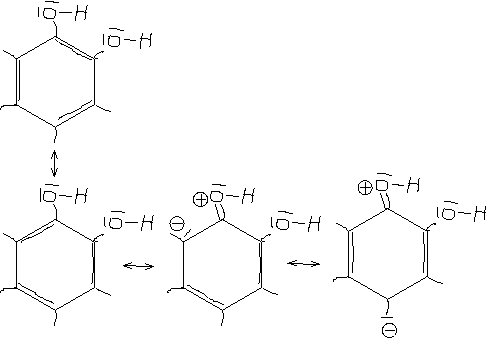

Mesomeriestabilisierung von 1,2-Dihydroxybenzol

[Man kann beim Aufstellen mesomerer Grenzformeln eine negative Ladung nur an Substituenten setzen, welche H sind (Platzgründe: ansonsten zu große Reste)]